Posted by Edd Mann on Oct 28, 2015

Asynchronous Calls within Flux

The Flux architecture abides by a single unidirectional data-flow throughout the entire application. This provides us with a host of benefits, ranging from easier to reason about code, to clearer testing strategies. However, one issue we faced in our recently updated interface tradesmen use to communicate with customers, was how to handle asynchronous calls within these constraints. Throughout this post I wish to guide you through the iterative design decisions made, along with the resulting abstractions and boundaries.

Basic Component Example

There is a common use-case within client-side applications to both push and fetch data from an external resource asynchronously. In the contrived component below we provide the client with the ability to act upon the enter-key being hit with a supplied submission handler.

class TaskInput extends React.Component {

const ENTER_KEY = 13;

_handleSubmit = (e) => {

if (e.keyCode === ENTER_KEY) {

this.props.onSubmit(e.target.value);

}

e.preventDefault();

};

render() {

return <input type="text" onKeyUp={this._handleSubmit} />;

}

}Asynchronous Calls within Components

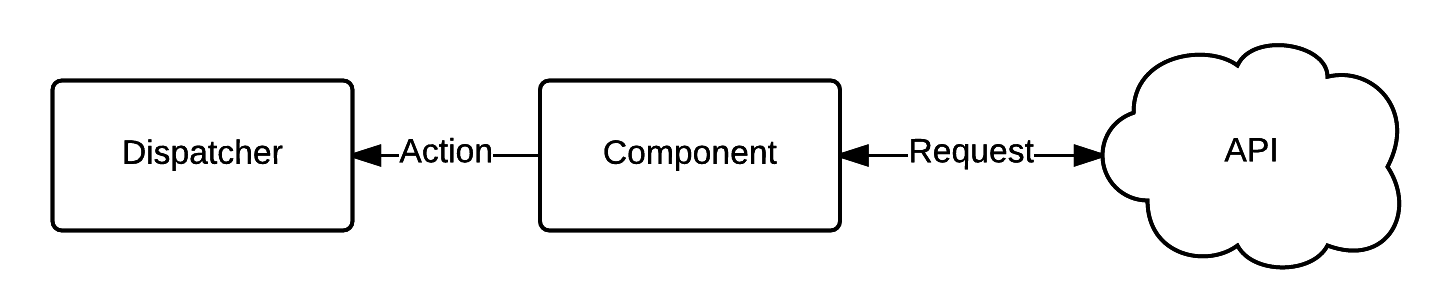

We initially decided to keep the asynchronous call and response logic within the component itself. This included the dispatch of either a success or fail action upon handling the result - due to external resource concerns (i.e. network issues, server-based validation) we could not be sure that a successful path would always occur.

const postJson = (endpoint, payload) =>

fetch(endpoint, {

method: 'post',

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json' },

body: JSON.stringify(payload) });<TaskInput onSubmit={message => {

postJson('/post', { message })

.then(task => dispatch({ type: 'RECEIVE_TASK', task }))

.catch(err => dispatch({ type: 'TASK_ERROR', error })) }} />

Although the above paradigm worked, we noticed many issues arise from its presence.

The first of which was how all the logic had now been co-located within the view layer.

You could question, that at this level is it necessary to know of these low-level details - about how we were submitting a task.

More strongly put, creating and handling the external resource request did not seem to be a responsibly of the component at all.

This coupling in turn made it harder to test the components behavior, as now to validate that a submission is sent we were required to provide an environment where (the implementation detail) fetch is present.

Finally, the component itself was the only member of the system that knew of the clients desire to add the task.

It is not until the request had been resolved or rejected did we let the dispatcher (and in-turn the system as a whole) know about this intent and resolution.

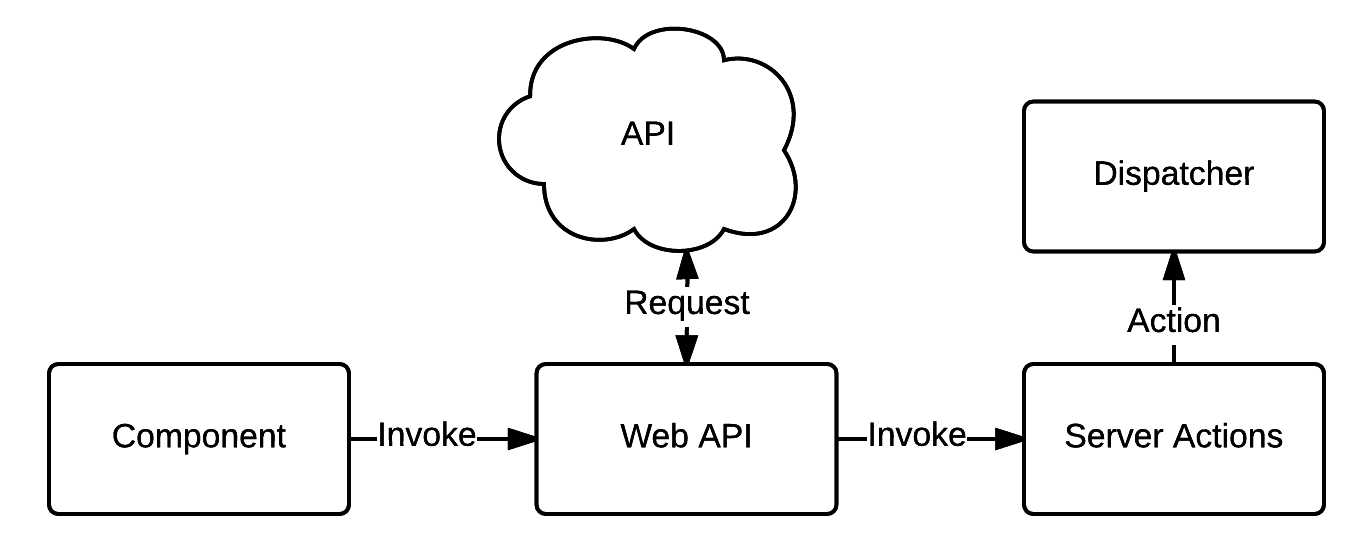

Web API and Action Creator Addition

To begin trying to resolve these highlighted issues we decided to first abstract out the two raw dispatch calls into an ‘Action Creator’. This allowed us to devise a clean API which did not concern the callee of what dispatch calls etc. were being fired in response to their invocation.

class ServerActions {

receiveTask(task) {

dispatch({ type: 'RECEIVE_TASK', task });

}

taskError(error) {

dispatch({ type: 'TASK_ERROR', error });

}

} Using this Action Creator we then went about abstracting out the external API call into an ‘Web API’, supplying the available server actions at runtime. This provided us with the ability to easily swap out real actions with test doubles, validating the correctness of API calls within the testing phase.

class WebAPI {

serverActions;

// ...

addTask(message) {

postJson('/post', { message })

.then(task => this.serverActions.receiveTask(task))

.catch(err => this.serverActions.taskError(error))

}

}With the addition of these two members, we could simply replace the submission logic found in the component with a call directly to the Web API. This refactoring made it easier to now test the component in isolation as well, with only a Web API test double instance being required.

<TaskInput onSubmit={message => webApi.addTask(message)} />

However, there were still issues that persisted after this refactoring. Still the component and now additionally Web API, were the only ones aware of this action being carried out within the system. At present, there was no way of providing the user with an optimistic representation of what the application state would look like - not until the response had been returned.

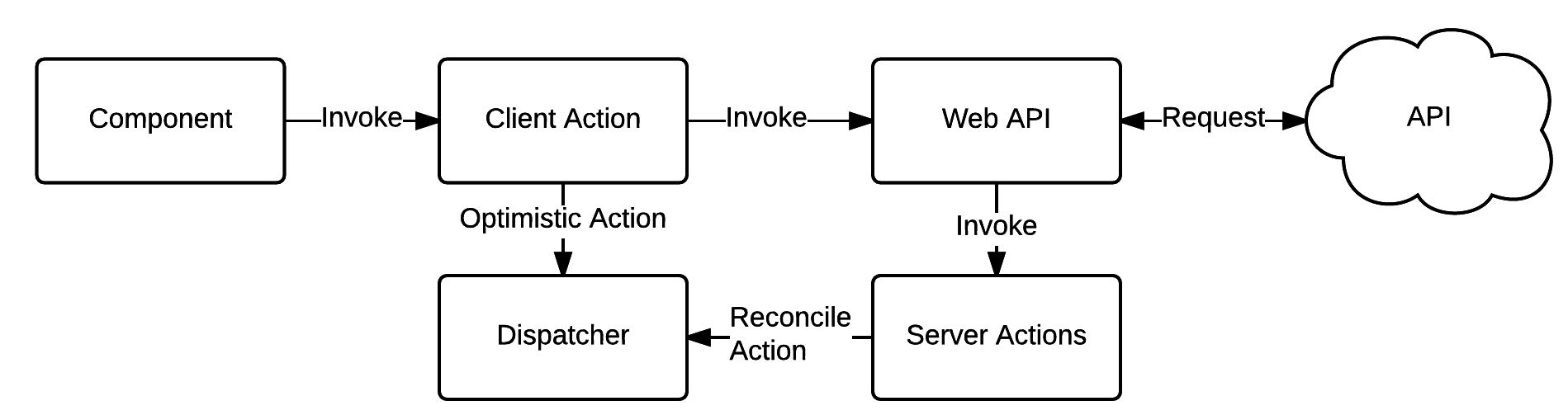

Optimistic Asynchronous Calls

At present, as we are not sure when the asynchronous call will return, we did not notify the system of any event until the promise had been resolved or rejected. However, we felt that it would be a far better user experience to optimistically apply the request to the current client state and reconcile this action when the asynchronous event returned.

To achieve this we decided to abstract out the call made to the Web API into its own action creator. We then dispatched a new action which, provided with a unique client id, optimistically performed the resulting resolution. It would then go about calling the Web API as per the previous implementation.

class ClientActions {

webApi;

// ...

addTask(message) {

const clientId = uniqueId();

dispatch({ type: 'ADD_TASK', clientId, message });

this.webApi.addTask(clientId, message);

}

}Looking at the implementation above you will notice that we generated a random clientId which is used to temporary identify the created resource until the external API provides us with an canonical id.

The Web API and server actions were in-turn required to be altered to cater for this temporary identifier.

Stores that were concerned with this action could add the pending resource as they desired, maybe including it with appended meta information (i.e. status: ‘ADDING’).

Finally, when the result from the asynchronous request had been received, the stores could go about reconciling their state i.e. replacing the temporary id with the supplied one or removing it if there had been an error.

class WebApi {

serverActions;

// ...

addTask(clientId, message) {

postJson('/post', { message })

.then(task => this.serverActions.recieveTask(clientId, task))

.catch(err => this.serverActions.taskError(clientId, error))

}

}We could now access the updated task action by way of the client actions creator abstraction.

<TaskInput onSubmit={message => clientActions.addTask(message)} />

To conclude, this final refactoring allowed us to clearly visualise and work within specific boundaries of the application, all with there own rates of change. We have found a significant ease in testing areas of the application in isolation, as well as a far easier to reason about mental model. Below is a list of some of the key strengths within testing that we have found since incorporating this model into our architecture:

- We can easily validate the correctness of Components contractual calls to Client Actions.

- Client Actions can be tested by assertion of store state after they have been invoked, along with their contractual calls to Web APIs.

- The Web API can be tested that it works with the external resource, by way of what is returned to the Server Action methods.

- The Server Actions can be invoked and application store state asserted for the correctness of their actions.

If you wish to see a full example of these concepts in practice, you can checkout the task-app repository on GitHub.